Antarctica Animals: Wildlife Guide to Antarctica Cruises

Penguins, seals, whales, and more. Antarctica animals have developed plenty of ways to deal with life in an inhospitable environment.

The animals of Antarctica are, rather unsurprisingly, quite a hardy lot. However, the only creature tough enough to endure life this far south all year long is the elusive and majestic Emperor Penguin (more on this super-Antarctic hero later on). Almost all of the incredible animals one encounters on a cruise to Antarctica must migrate here at the beginning of every southern spring.

They swim and fly for thousands of kilometres, feeding on krill (but mostly each other) to reach the glorious shores of the Antarctic Peninsula. Once here, they must contend with harsh living conditions – from overcrowded nesting sites to stiff competition for a decent feed – all in arguably the remotest and most inhospitable place on earth – Antarctica.

Well, for us humans, at least.

Yes, Antarctica may often be dubbed ‘the most inhospitable place on earth, but there are quite a few species of wildlife that may argue this, though we doubt many would get offended. After all, when you live in a world where -2 degrees Celsius is considered ‘balmy’, you may develop a thick skin.

The Animals of Antarctica

Want to come and meet some of these incredible creatures? Then don your outwear (obvs), put on your gloves and scarf and head to Antarctica.

Here are just some of the most awe-inspiring creatures you may meet at the end of our world.

Everybody Loves Penguins

Think Antarctica. Think penguins. Penguins are arguably the most well known Antarctic Wildlife. They look adorable and, occasionally, fluffy, but they are surprisingly tough. They are birds, but they can’t fly. Their “wings” are essentially small flippers that can efficiently propel them over great distances underwater: watch a movie of penguins underwater, and it looks remarkably like flight.

But not so on land where short legs lead to awkward waddles, especially when the surface is steep or rough. However, in soft snow or slippery ice, they can “toboggan” on their tummies, pushing with their flippers and feet. They come ashore only to nest – all their food is in the sea, and they will travel great distances over the ice to get to the sea, then great lengths in the water looking for krill, squid and fish.

Below are the most common penguins you’ll encounter on an Antarctic Peninsula cruise. Please read our dedicated penguin blog for an in-depth look at all species of penguins, including those living in Antarctica and the Sub-Antarctic Islands.

Emperor Penguins

The Emperor penguin is not only one of the hardiest creatures you’ll ever come across but, possibly, one of the most beautiful too. Born with a super cute fluffy fur that insulates it from the cold, the Emperor is born in springtime (hence breeding in winter) so it can spend its first summer feasting abundantly. Its thick coat is the only thing that’ll allow it to survive its first winter.

The built-in doona with which they are born is excellent on land but kind of sucks in water, so chicks must shed before they ever take to the sea. Emperor Penguins are true team players and waddle close together to soak in collective warmth in the winter months. This giant huddle is one of the most fascinating wildlife spectacles on earth.

Encounters with Emperor penguins are rare and most commonly occur in the East Antarctic region, so if they’re at the top of your must-see list, you may need to travel to this rarely visited part of Antarctica. If heading only to the Antarctic Peninsula, you’d have to be extremely lucky to see an Emperor.

But, if you do, it’ll undoubtedly be the highlight of your entire trip.

Adelie Penguins

If ever there was a size vs fierceness correlation in the animal world, it’s certainly bypassed the Adelie, a creature whose struggle to survive starts from the moment it hatches. Mother Adelies typically lay two eggs simultaneously, with the ‘survival of the fittest’ starting from when the two fledglings emerge. Only one will survive the first week of life and, at just three months of age, it will leave the colony sea-bound and won’t return until it’s ready to breed, about four years later.

Being the smallest penguin in Antarctica means the Adelie has plenty of predators, but it has also developed a seriously feisty attitude. Watch out for this guy: get too close, and you’ll be sure to hear all about it.

Chinstrap Penguin

The most recognisable penguin in Antarctica, the funny-looking chinstrap, is only marginally larger than the Adelie and are often found floating on icebergs out in the open ocean. They can literally pop up anywhere! The most abundant penguin species in the southern continent, their colonies can number in the hundreds of thousands and can be found in the South Shetland Islands and on the Antarctic Peninsula proper.

Unlike the hardy Adelie – who breeds in Antarctica and hangs around all year long – the chinstrap prefers to head north of the sea ice during the winter, returning to breed between October and March every year. The largest colony of chinstrap penguins is found on the South Sandwich Islands, famously home to over 1.2 million furry little guys. Overall, they are believed to be the most numerous of all penguins, with an estimated 7.5 million individuals found in the southern seas.

Gentoo Penguin

The third-largest penguin in Antarctica (after the King and Emperor), the gentoo stands out from the crowd with its red beak, orange feet, and distinctive strut. Reaching just over 90 cm in height, the gentoo is a stunning swimmer, reaching speeds of up to 30km/hr, making it the fastest diving bird of all!

Seals

These widespread, fin-footed creatures love cold water and can be found throughout the Antarctic regions. Commonly spotted lounging about in the picturesque areas of the world, these Antarctic seals are fearsome predators for fish, squid, molluscs, crustaceans, and penguins!

Leopard Seal

Yes, everybody loves penguins – and so do Leopard Seals. While not the largest seal in the Antarctic, the leopard seal is one of the most formidable Antarctic hunters of all and awe-inspiring.

Females can reach up to 500kg in weight and 3.8m in length, a breathtaking size indeed. It can stay underwater for up to 15 minutes at a time, something it does when it plans a surprise attack on unsuspecting penguins. Not surprisingly, whales are the only known predator of this arduous creature.

Weddell Seal

Only slightly smaller than leopard seals, although with a much smaller head, the Weddell species is a much more placid animal that doesn’t like to veer too far away from their breeding colony. They’re renowned for being the mammals that live further south than any other and are considered one of the hardiest Antarctic wildlife of all.

Astonishingly, Weddell seals can dive underwater for up to 80 minutes, which helps them travel underneath pack-ice to find the ideal spot to break through for a breather. Weddell seals spend the entire winter underwater and only come up for air when they need to to avoid the harsh Antarctic winds. For all of these incredible reasons, the Weddell is also the most studied seal of them all – and possibly the cutest too!

Crabeater Seals

The most abundant seal in Antarctica is the crabeater, whose numbers in summer can reach 15 million! Although they don’t spend winters on the peninsula, the crabeater does spend its entire lifespan in the Antarctic region, covering humongous distances every season. Like to take a wild guess what the crabeater feeds on?

That’s right: prawns!

Southern Elephant Seal

The Mirounga Leonina may have drawn the short end of the straw in the looks department, but don’t let that fool you. He more than makes up for what he lacks in aesthetics in sheer gargantuan size and fierce brutality, albeit very rarely (the latter, not the former).

The largest of all seal species, the southern elephant male can weigh up to an impressive 4 tonnes, whilst the more svelte ladies usually weigh in at about 800kg. That peculiar trunk at the end of a male seal’s snout is air-inflatable. The bellowing trumpet that the animal can produce is reminiscent of an elephant’s trumpeting, hence its common name.

Elephant seals live in harems, with one beach master (the almighty male king) overseeing a group of several dozen females. Although you may be thinking ‘lucky devil’ right now, take note that protecting all those females from the aggressive competition is hard work, especially when you’re made up of 90% blubber. Southern Elephant Seals are often seen on cruises heading over to South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands.

Read more about Antarctica seal species and where you’re likely to see them.

Whales

Whales are the largest known animals in the world are an essential part of the Southern Ocean and Antarctic ecosystems and spend at least half their lives in Antarctica.

Blue Whales

Blue whales are the giants of the sea and the giants of the universe. A blue whale can be up to 30 metres long (well over the length of B-Double trucks you’ll see on the road) and over 180 tonnes (some four times the weight of that loaded truck). While rare, they are sometimes seen feeding near the ice edge.

Humpback Whales

The most abundant baleen whale in the region, the Humpback is an absolute delight to admire due to being one of the most active. They love breaching, slapping the water with fins and tail and often put on a bit of a show for onlookers. In Australia, migrating Humpbacks are a popular sight along the eastern coastline in winter, which is where they head to breed after spending the summer feeding in the waters of Antarctica.

Humpbacks are perhaps the least ‘graceful’ of all the whales and tend to be slow swimmers due to their very un-ergonomic (i.e. fat and stocky) shape, but they certainly are among the most gracious. Not only are they slow enough so boats can keep up with them, but welcoming enough to tolerate close(er) encounters. This makes them among the most adored subjects on Antarctica cruises.

Killer Whales

The orca or killer whale is an exceptionally intelligent animal known for its tall fin and the striking contrast of its black and white markings. It is the only cetacean that regularly feeds on other warm-blooded animals. It is really the largest of the dolphins, of which there are many species in southern waters along with beaked whales.

The killer whale’s favourite hunting grounds in summer are the coastal areas of Antarctica. As numbers can be as high as 7,000 per year, chances you’ll see one on an Antarctica cruise are pretty good.

Predatory and migratory, the killer whale can cover astonishing distances every season, reaching opposing ends of our planet in mere months. Few sights are as breathtaking as that of a killer whale gliding in the wake of your Antarctica cruise ship. Even more impressive is witnessing a gang of killer whales fishing for seals en masse.

Seabirds

Iconic seabirds such as albatrosses and fulmars spend nearly all of their lives at sea, settling briefly on the sub-Antarctic islands only to reproduce. The Southern Ocean is so large that it can support a vast number of seabirds, although the few breeding sites become very crowded. Antarctica is a true paradise for anyone who enjoys birdwatching.

Despite the wild seas of the Southern Ocean, some surprisingly small birds are also encountered, such as the tiny Wilson’s Storm Petrel, which flutters about the surface as it feeds. On land in Antarctica can also be found the beautiful white Snow Petrels, which come ashore to nest in rock crevices.

Other common seabirds include the smaller species of albatross, fulmars, petrels, skuas and prions.

Wandering Albatross

Over 100 million birds head for the rocky shores of Antarctica every spring. Out of all of those, perhaps the most majestic of all is the wandering albatross. Boasting the largest wingspan of any bird on earth, up to 3.5 metres, the wandering albatross is so named for its penchant for travelling very long distances. This incredible bird covers great distances in what looks like effortless flight with long sweeping glides on its fully outstretched wings.

Wanderers roam across the Southern Ocean, sometimes as far south as the edge of the pack ice but mainly around the food-rich Antarctic Convergence. They are often seen following in the wake of ships but can be killed if they catch the bait of Antarctic fishing vessels.

From the Largest to the Smallest – Plankton, including Krill

All of these large animals, whales, seals, penguins and other seabirds, find their food in the Southern Ocean. At the bottom of the food chain are the microscopically small single-celled organisms that drift with the ocean currents. Plankton are produced in huge numbers and thus provide food for the higher levels. A key organism is krill. Krill are also planktonic, and they feed on the phytoplankton. Krill is a target species for many species of higher animals, including the great whales that scoop up vast quantities of this protein-rich food source.

How Antarctic Animals Cope with the Harsh Conditions?

The wildlife of Antarctica has collectively developed plenty of coping mechanisms over time, each peculiarity specific to a species, helping creatures hold on to their body heat, primarily.

Wind & waterproof coats

On an Antarctic cruise, you’ll soon realise that an essential item of clothing down here is the high-tech outerwear you’ll be supplied with before every Zodiac excursion on land. Your body does a fine job of making its own heat, and your mission, each and every time you head outdoors will be to hang on to that, come rain, hail, or snowstorm.

And so it is with Antarctic wildlife, who’ve developed exceptional outer layers, none more impressive than that of the Emperor Penguin, who boasts four layers of scaled feathers, which helps it stand tall and strong even in the harshest of blizzards. The waddle is a natural consequence of all the layers, as you may well imagine.

Thick layers of body fat

In our world, an abundance of body fat is seen as detrimental to our health but, in Antarctica, it’s an intelligent evolutionary move and pivotal for survival. Fat is a fantastic insulator, so the more is definitely, the merrier down in these icy lands. You may not want to look like a male elephant seal, but boy, you’ll surely want to be as insulated as one if you lived here. Plus, you’ll live comfortably on your own fat if food is scarce, so, you know, that’s a pretty nifty party trick anyway.

Small hands, feet and noses

Alongside your outer jacket and pants, your most valued item of clothing on Antarctic expeditions are going to be your thermal socks, scarf and, perhaps more importantly than anything else, your insulated gloves. That’s because it’s much easier to lose heat via your extremities than it is via your well-padded torso, so you won’t want to keep those escape hatches open for very long once the wind starts howling. Antarctic wildlife evolved smaller limbs and beaks precisely because keeping the extremities smaller (than usual) allows seals and penguins to hold on to their heat even more efficiently.

Larger sized, overall

The most astonishing aspect of an Antarctic cruising experience is coming face-to-face with the unique creatures that live down here and finally realising how big they are. It figures that being small and dainty probably won’t bode well for your survival in this kind of climate but, seriously, coming eye-to-eye with a 70cm-tall, 5kg-hefty Adelie Penguin is pretty awe-inspiring and, mind you, that’s the smallest penguin you’ll see in Antarctica. And it’s still about twice the size of its Galapagos cousin.

Generally speaking, the wildlife of Antarctica is larger in size than any of their counterparts found in other regions of the world, and this too is an evolutionary trick to help them cope with the harsher conditions. Large and heavy means less surface area from where heat can escape, so chunkiness and tallness are favourable traits for survival. This explains why the Emperor Penguin, the only one of its kind able to thrive in Antarctica over winter, is the largest and heaviest of all penguins and the one who has the smallest beak, given his enormous size.

We talk about evolutionary adaptations of Antarctica’s wildlife because, contrary to popular belief, hardy creatures like penguins didn’t actually evolve in cold climates. They may be associated with icebergs and ice floes (and even ice creams) nowadays, but these are some of the most ancient creatures on earth, who appeared on our planet long before the ice caps were ever formed, in much warmer climates, in fact.

Surely there is something Living only on land!

Humans have occupied Antarctica parts of Antarctica for over a century – but in small numbers. In winter, the human population is perhaps 5000 people. Humans are temporary visitors as it is not a natural environment for us. But there is some Antarctic Wildlife that calls Antarctica home and never leaves. These are wingless midges (insects) that inhabit the rocks and beaches of the Antarctic Peninsula – dormant over winter and active only for the brief summer window. They are up to 5mm long and can survive being frozen for as much as two years. They may not be particularly photogenic, but they are true Antarctic citizens. All the other creatures spend most of their lives in the Southern Ocean or come across it to reach Antarctica.

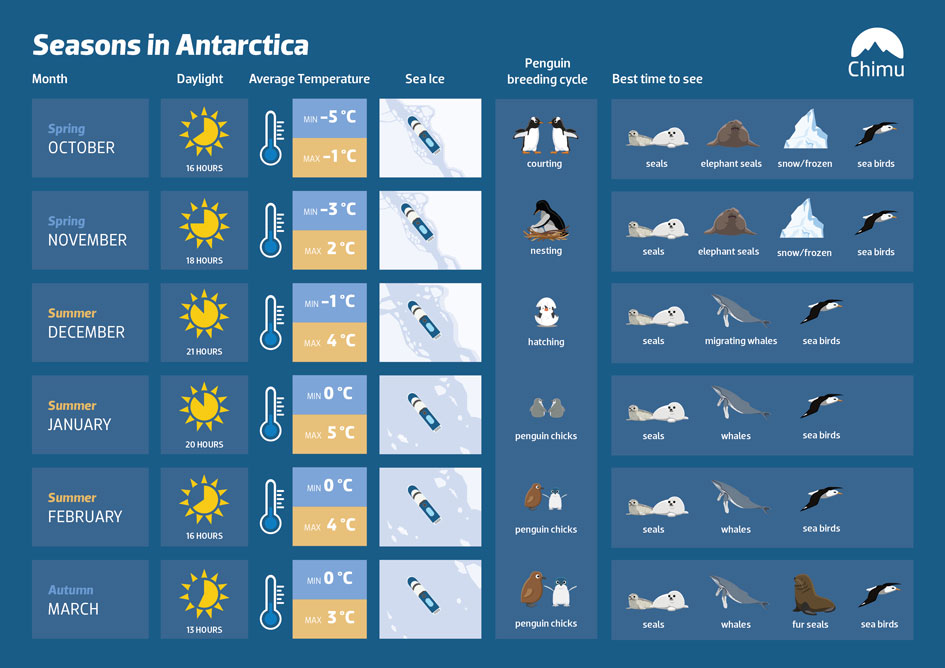

When to go to Antarctica

Infected with Antarctica fever yet?

An Antarctica cruise takes you to one of the last untouched destinations on earth. This unique continent provides a truly life-changing, immersive and wildlife-rich experience of a lifetime. Antarctica – you deserve it!

Talk to one of our experienced Destination Specialists to turn your Antarctic, Arctic and South American dream into a reality.

Contact us